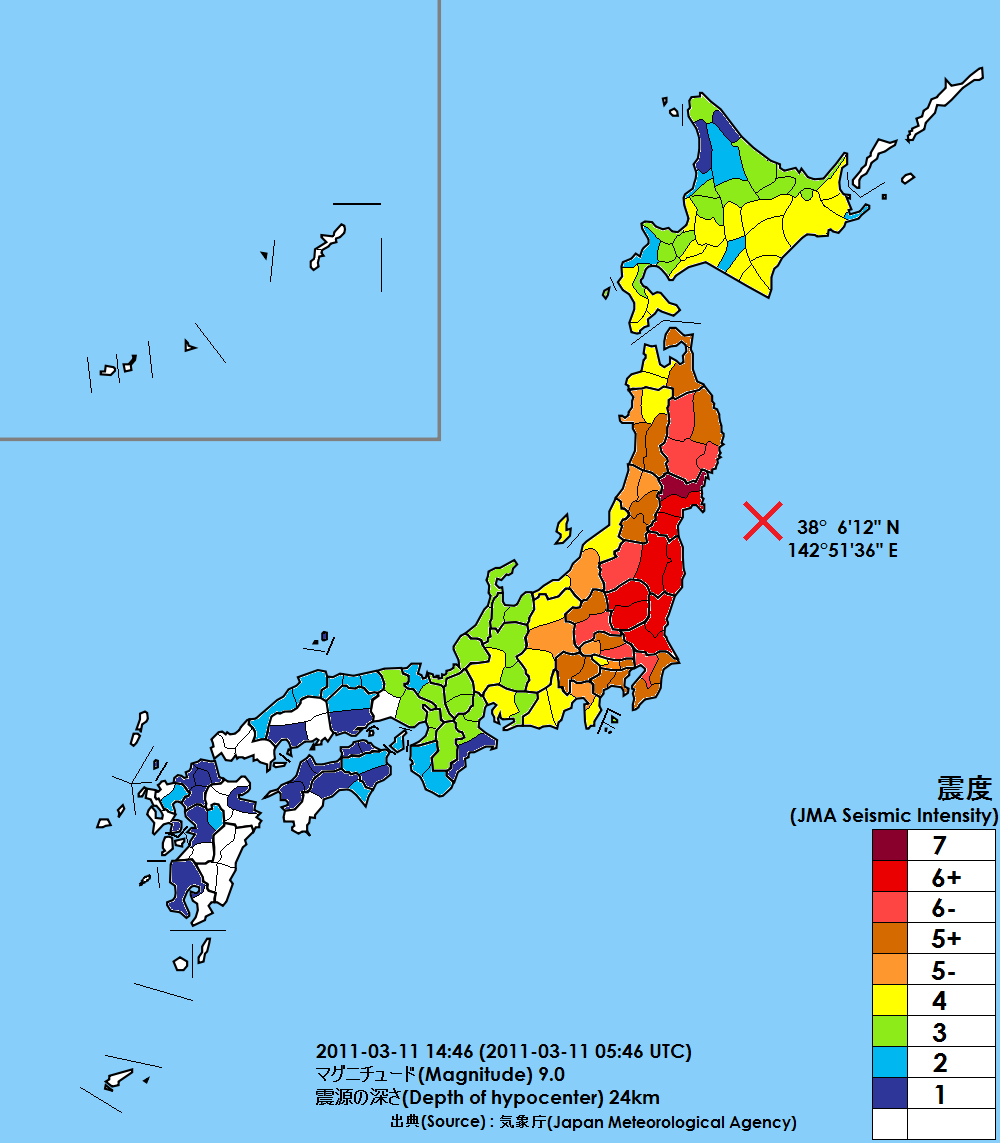

On this day in 2011, I was leaving my office in Yūrakuchō, Tokyo, for a dreaded afternoon meeting with a big systems integrator company. As I walked past the reception desk in the lobby and towards the elevators, I glanced up at a TV screen and saw a map of Japan with a big red X to its northeast.

Anyone who has lived in Japan is intimately familiar with these images. They are broadcast every time a “significant” quake occurs, but hardly anyone blinks due to complete confidence in modern building construction codes. You enjoy (or ignore) the rumble when it arrives, and then continue on with your day without giving it a second thought.

A couple of seconds later, though, this particular X made its presence known. No rocking cradles or light shivers this time: the violent shaking literally knocked everyone off their feet, with people screaming in terror as we grasped for walls in futile attempts to balance ourselves. The huge building I was in suddenly did not feel so stable; I honestly thought it would topple over, flinging me through the huge office kitchen windows, and out over the tracks of Yūrakuchō station.

Fortunately, those construction codes held up, and after a few of the most intense minutes of my life, the still upright building’s emergency systems kicked into gear. Elevators were disabled, so we hurriedly descended down the stairs from the twelfth floor in hopes of getting to ground before any potential aftershocks hit.

The streets were full of calm but confused people. Mobile phone networks were jammed, leading to massive, but orderly, queues outside public phone booths. 3G internet was still usable, though, so social media (Facebook only for me at the time) became the only usable method for real-time communication.

After confirming our colleagues were out of the building, we all agreed that work time was over, and we should make sure our homes and loved ones were safe. So, at least I got out of attending that wretched meeting…

However, trains had stopped, bus stop queues were longer than those for phone booths, and roads were at a complete standstill. All normal traffic rules had been disregarded, as streets became pedestrian footpaths, and I merged in with them for my long walk home across Tokyo.

As I passed Shimbashi Station, I joined a huge crowd of people that had gathered around a big TV screen broadcasting the news, and could not believe what I was seeing.

The images of a tsunami barreling through rural northern Japan and annihilating everything in its path felt surreal. It took a moment to process that this was indeed reality, and not a scene from Deep Impact or The Day After Tomorrow. After a few minutes, I snapped out of my stupor, picked my jaw up off the ground, and continued walking.

My partner, Naoko, was out with friends for the day, and did not use newfangled social media, so getting in direct contact with her was not possible. After a couple hours walk, I managed to find a lonely public phone without a queue, and called her mother on the other side of the country. If Nao reached out there, I wanted her to know that I was safe, and that we should just try and meet back at our apartment.

We had not planned for a natural disaster scenario of this magnitude, and hence did not have emergency kits or food rations on-hand. I wagered we had enough supplies to last us a week (maybe…? I had never had to judge that before…), but just to make sure, I stopped by several convenience stores and supermarkets, only to be greeted by rows of empty shelves. The city had already been cleaned out.

I arrived home to discover my bicycle discarded in the park opposite. Someone had tried to steal it (first time ever), but the cheap lock had been enough security to move them on. Given the circumstances, I would not have minded if they succeeded.

My apartment building was still standing, and inside, no damage at all. All I could do now was wait: wait for the phone network to come back online, wait for Nao to get home, wait for news about what was going on…

The next couple of days were punctuated by constant aftershocks. The haunting chimes from the Earthquake Early Warning system gave us a few seconds notice to brace ourselves before another round of ground turbulence. It would have been a luxury if another huge earthquake was the only thing we had to worry about, but all the news about problems at nuclear power plants had us anxious about whether we were actually witnessing the literal end of Japan.

At the very least, the possibility we would have to flee from Tokyo felt very real, so we packed some bags full of basic necessities, and left them by our front door, ready to go should we need to leave quickly.

When images of Fukushima Daiichi’s Unit 3 Reactor hydrogen explosion flashed across our screen on the afternoon of March 14, we felt the overwhelming need to go. It was too late to get on a shinkansen, so we left first thing in the morning to just head west, and away from it all.

The strangest thing about going to the station and catching a train was just how normal it felt. A literal explosion occurred at a nuclear power plant just hours before, and there were not hordes of people cramming the carriages to get out of the city. Were we overreacting…?

The air of calm certainly gave me some pause, but if the situation got worse to the point of everyone in Tokyo/eastern Japan actually needing to evacuate, a scenario that seemed less far-fetched with every passing moment, I felt we would not get a second chance at such a smooth run out of the city.

Arriving in Kōchi was like entering a different universe, where the earthquake had not happened, supermarket shelves were still full, and life was peaceful. It was impossible to permanently ignore reality, of course, and we were glued to all media for any morsels of information about the crisis.

I recall television just constantly playing strange cartoons, pushed by Ad Council Japan, that extolled the value of greetings and other Japanese virtues using animal puns, and thinking it to be a strange panic mitigation/population distraction strategy. Oh, you wanted actual news about the current existential threat? Nope, here’s literally that same cartoon again. And again and again.

Want to trigger someone who lived through this event? Play them the following video.

The next week was mostly a blur, but as it gradually became apparent that the worst case scenario probably would not happen immediately, my employer’s gentle hints about considering getting back to work in the Tokyo office became concrete orders to return. So, we begrudgingly left our rural retreat, hoping for the best.

Essentials in the city were still in short supply, as efforts and resources were deservedly redirected to the areas up north directly affected by the disaster. I remember bottled water was impossible to find (and it was uncertain how drinkable Tokyo’s water was), so we had to get it shipped from Kōchi. This worked for a while, until everyone else with family outside Tokyo followed the same strategy, contributing to more supply shortages country-wide. But, obviously, put into perspective, we managed just fine.

The earthquakes/aftershocks had not dissipated during the week we were away, and you can bet every warning that flashed up on the screen now got our full attention.

We now viscerally understood that although we may have to worry about how to deal with the immediate consequences of a large earthquake, we would also have to consider whether it is also a harbinger of further quakes to come.

For example, just two days before the big one hit…

Oh, you sweet summer child…you would not believe what’s in store next…

Naoko and I ended up leaving Japan permanently at the end of 2011, as we were definitely ready to try something new. But, living through this period certainly instilled in us a newfound respect for the indifferent destructive forces of nature, and the impermanence of physical things.

We still love visiting Japan, and go back regularly. But, if we ever end up living there again, we like to think we will be much better prepared for disasters, and certainly provide our full attention to all the inevitable earthquake warnings.

Leave a comment